Glacial melting in Switzerland was once again enormous in 2025. A winter with low snow depth combined with heat waves in June and August led to a loss of three per cent of the glacier volume. This is the fourth largest level of shrinkage since measurements began. Consequently, the ice mass reduced by one quarter in the last ten years. This was reported by GLAMOS, the glacier monitoring network in Switzerland, and the Swiss Commission for Cryosphere observation (SCC), in which the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF is also represented.

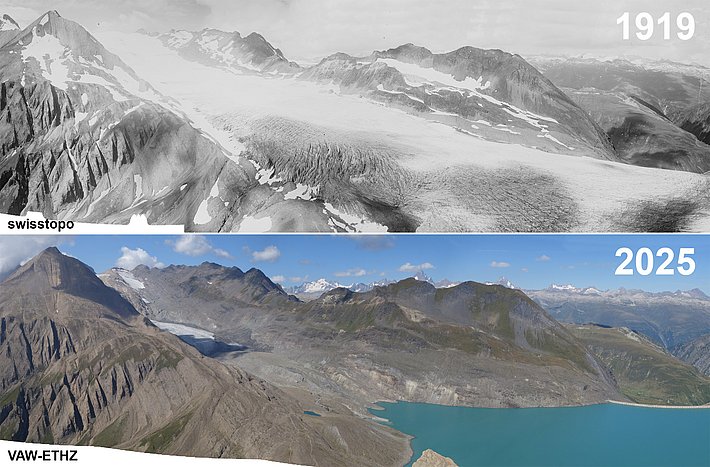

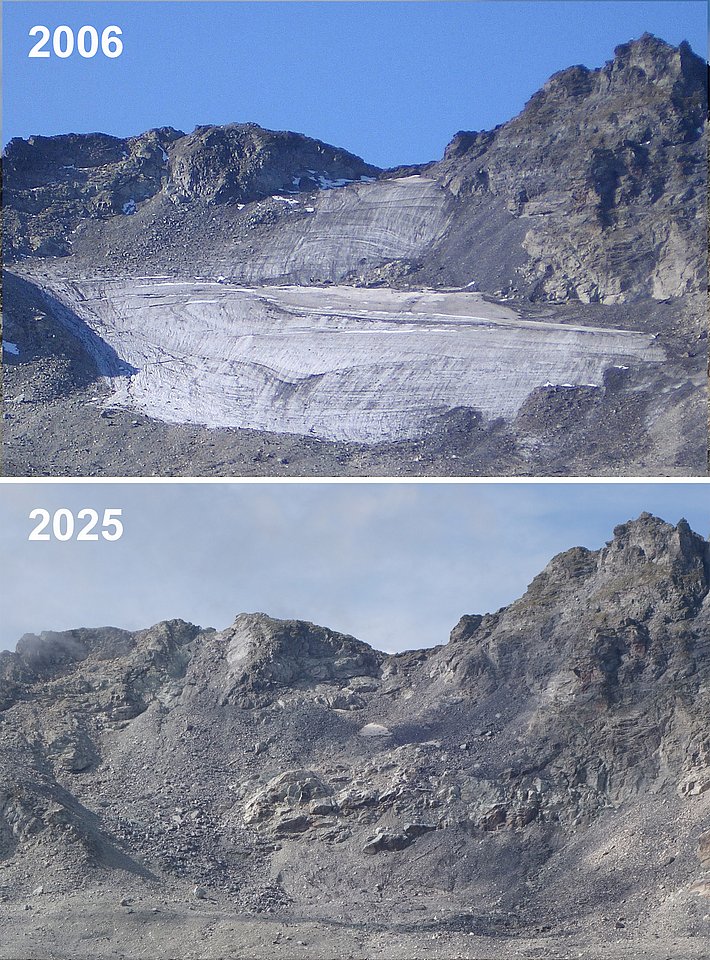

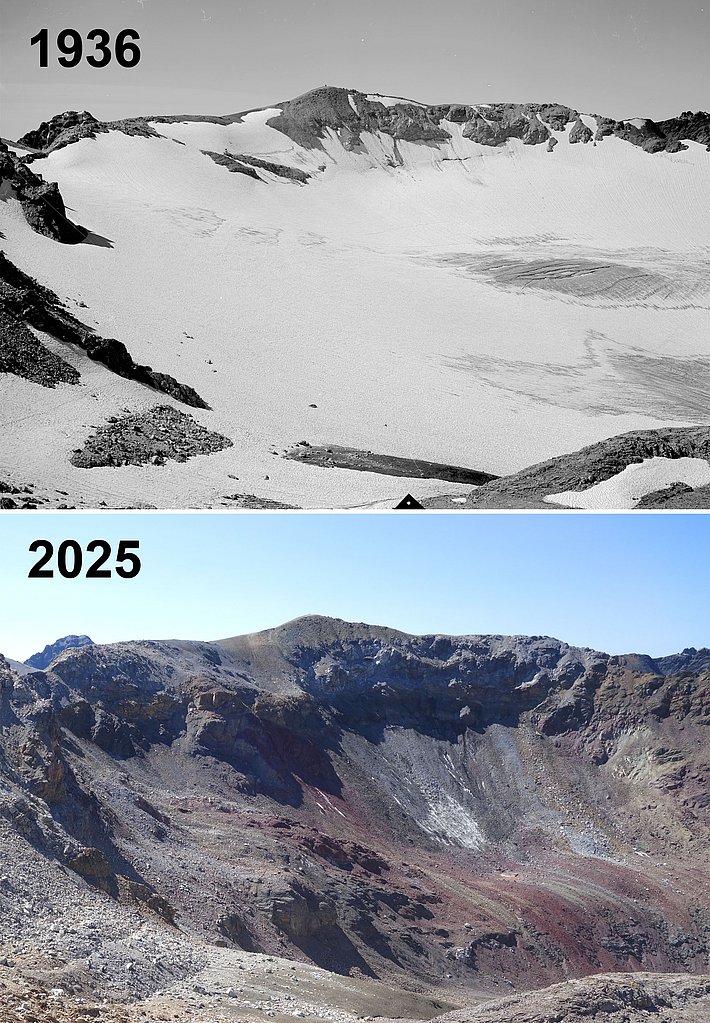

Even the United Nations International Year of Glaciers' Preservation has seen further massive melting of glaciers in Switzerland. A winter with little snow was followed by heat waves in June 2025 that saw glaciers nearing the record levels of losses of 2022. Snow reserves from the winter were already depleted in the first half of July, and the ice masses began to melt earlier than had rarely ever been recorded. The cool weather in July provided some relief and prevented an even worse outcome. Nevertheless, almost a further three per cent of the ice volume was lost across Switzerland this year, and this is the fourth greatest shrinkage after the years 2022, 2023 and 2003. 2025 therefore importantly contributed to the decade with the most rapid ice loss. Glaciers all over Switzerland have lost a quarter of their volume since 2015. Over 1,000 small glaciers have already disappeared.

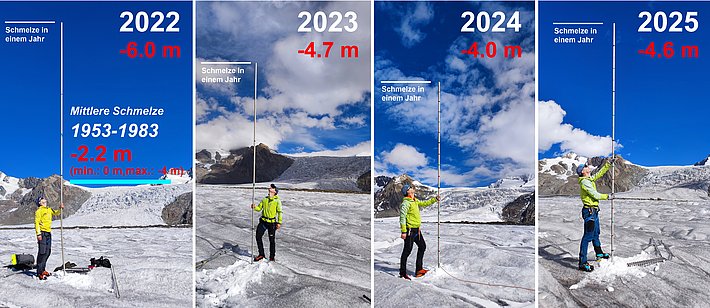

In particular, glaciers below 3,000 m above sea level have suffered considerably in 2025. Snow from the winter disappeared there up to the summit level. As a consequence, the ice thickness on, for example, the Claridenfirn (Canton of Glarus), the Plaine Morte Glacier (Canton of Bern) and the Silvretta Glacier (Canton of the Grisons) reduced by over two metres. For glaciers in the southern Canton of Valais, such as the Allalin Glacier or Findel Glacier, the loss was less at around one metre.

Too little snow in winter ¶

In the winter of 2024/2025, the combination of less precipitation and the third warmest six months of winter (October to March) since measurements began led to very low snow depths, as shown by measurements taken by the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF. For example, less fresh snow fell in parts of the northern and central Grisons than ever before. For this reason, around 13 per cent less snow was evident on the glaciers at the end of April when compared to the period from 2010 to 2020. The second warmest June since records began led to rapid melting of snow right up to the highest altitudes. Following a somewhat cool and damp July, August brought a heatwave with a high zero-degree line recorded in part at over 5,000 metres. In combination, this weather led to above-average temperatures in the summer. Between July and September, a few cold fronts resulted to individual days with fresh snow over 2,500 m above sea level, but this only remained for longer periods in high mountains.

"The continuous diminishing of glaciers also contributes to the destabilising of mountains," says Matthias Huss, Director of GLAMOS. "This can lead to events such as in the Lötschental valley where an avalanche of rock and ice buried the village of Blatten."

The Swiss Commission for Cryosphere observation (SCC) ¶

The Swiss Commission for Cryosphere observation (SCC) of the Swiss Academy of Sciences (SCNAT) documents changes in the Alpine cryosphere. It coordinates the long-term Swiss monitoring networks created for snow, glaciers (GLAMOS) and permafrost (PERMOS). The Swiss Commission for Cryosphere observation (SCC) therefore represents those institutions that look after national monitoring networks, such as the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL, the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF, the Swiss Federal Office for Meteorology and Climatology (MeteoSchweiz), the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH Zurich), the Universities of Zurich, Fribourg and Lausanne and the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland (SUPSI), or who contribute financially to long-term safeguarding, such as the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN), the Swiss Federal Office for Meteorology and Climatology (MeteoSwiss), in the context of the Swiss Global Climate Observing System (GCOS), the Swiss Academy of Sciences (SCNAT) and the Swiss Federal Office of Topography (swisstopo).

Contact ¶

Copyright ¶

WSL and SLF provide image and sound material free of charge for use in the context of press contributions in connection with this media release. The transfer of this material to image, sound and/or video databases and the sale of the material by third parties are not permitted.