14.01.2026 | Beate Kittl | WSL News

For 2999 endangered species, Switzerland has a special responsibility to ensure their long-term survival. They are listed on the new list of priority species, which was compiled with the involvement of the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL). Here are answers to the most important questions.

- In Switzerland, 2,999 species are now considered priority species – they are particularly dependent on protective measures for their survival, and Switzerland has a special responsibility for their conservation.

- The national data and information centres under Infospecies compile the list of priority species, which is legally binding.

- The list helps the federal government and cantons to make targeted use of limited nature conservation resources and to better coordinate species protection across all groups of organisms.

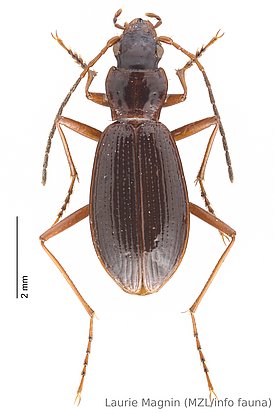

The western house martin, the Blüemlisalp ground beetle, the Insubrian gentian, the crystalwort, but also all bats found in Switzerland: 2,999 species are on the new list of priority species in Switzerland (German, French, Italian) and therefore need the most support from humans. It is compiled by the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) in collaboration with the national data and information centres organised under the umbrella organisation InfoSpecies. Its president, lichen expert Silvia Stofer from the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL, explains its purpose.

What is a priority species?

Silvia Stofer: These are species that need to be promoted in order to ensure their long-term conservation in Switzerland. A species is considered a priority if it is on the Red List and Switzerland has an international responsibility for its protection. Around 56,000 species have been recorded in Switzerland, and over 10,000 of these have been investigated in the federal government's Red List programme, from which about 3700 were classified* as threatened. From an international perspective, the conservation and promotion of populations in Switzerland is particularly important for just under a third of these species, for example because the species only occurs in Switzerland (is endemic). Common species that are widespread in Europe and non-native species are not classified as a priority.

Currently, the list of nationally priority species only includes those groups of organisms for which a Red List already exists. Data on these species is collected in national information centres and made available to the public. Two of these centres, SwissFungi and SwissLichens, are operated by the WSL.

Which species are these?

Stofer: The Snow mugwort and the Keist's Plump Grasshopper, for example, are only found in Switzerland globally; they are endemic species. Switzerland bears sole responsibility for the survival of these species, because if the population is damaged, they could become extinct globally.

We also bear a particularly high responsibility for partial endemics, which occur not only in Switzerland but also in neighbouring countries. These include, for example, the Engadin rock snail and Breidler's crystalwort. The extinction of such species in Switzerland would threaten their continued existence worldwide.

There are also species that are widespread in principle, but the areas in which they actually occur are often far apart. Their populations in Switzerland are important for connectivity and are therefore classified as priority species. These include many mosses, lichens and fungi.

What is the purpose of the list of priority species?

Stofer: The national priority list helps the cantons to focus on projects for the most urgent candidates in view of limited resources. It also forms the basis on which the federal government and cantons negotiate funding for nature conservation within the programme agreements. It provides guidance on which species require urgent measures and what measures are appropriate. This allows each canton to see how many nationally priority species occur there and what needs to be done.

The list of priority species has been available since 2011 as part of the Federal Office for the Environment's (FOEN) environmental enforcement series. This means that it is legally binding. Red lists have been established in the Nature and Cultural Heritage Protection Ordinance since 1991. The Swiss Federal Constitution stipulates that we must protect animal and plant species from extinction.

What problems do priority species face?

Stofer: Biodiversity is mainly lost through the destruction and fragmentation of habitats and the deterioration of habitat quality. That is why many moorland species, for example, are on the list. Other species cannot find enough nesting sites, such as the house martin, which nests under eaves, or need hedges as a connecting element for foraging, such as the polecat or the dormouse.

Only a few small populations are known to exist of other species, such as the Pink Waxcap, a fungus found in poor meadows and pastures. In order to preserve the species, it is important to secure existing populations as quickly as possible and to maintain the current form of land use at the site.

What can be done for these species?

This can be done on three levels: firstly, species can be directly supported with specific measures, for example by preserving and promoting host trees for the large lungwort. Secondly, the quality and connectivity of habitats can be improved so that the entire community benefits – for example, the rattle grasshopper needs open ground in extensively used dry and warm meadows and pastures. Thirdly, many species would benefit from the entire land area being used in a biodiversity-friendly manner – for example, by preserving and creating many more structures such as copses, ponds, dry stone walls, cairns and free-standing individual trees.

In future, we would like to shift the focus from measures for individual species, such as the capercaillie action plan, to instruments that cover several species and groups of organisms at the same time. The aim is to pool support measures for nationally priority species more effectively. Only with a broad-based approach do we have a chance of tackling the many tasks ahead and preserving biodiversity in Switzerland in the long term.

*Correction 15 January 2026: Of 10,000 species, around 3,700 are endangered, not 10,000.

The biologist Silvia Stofer is a research associate in the WSL Nature Conservation Biology Group. She heads the National Data and Information Centre for Lichens, SwissLichens, and is president of the umbrella organisation InfoSpecies.

* Copyright notice for bats: Please use images with the following image source reference: www.fledermausschutz.ch. The images may only be used for the above-mentioned purpose. The copyrights remain with the photographer or image author. The images may not be passed on to third parties without the consent of the image author. Media outlets may use the image free of charge, provided they comply with the above terms of use.

Contact ¶

Links and documents ¶

Liste der National Prioritären Arten der Schweiz (German, French, Italian)

Copyright ¶

WSL and SLF provide image and sound material free of charge for use in the context of press contributions in connection with this media release. The transfer of this material to image, sound and/or video databases and the sale of the material by third parties are not permitted.