12.11.2025 | Jochen Bettzieche | SLF News

SLF research on the Matterhorn shows how meltwater in permafrost can lead to rock slope instability – a consequence of climate change.

- Climate change destabilises rock: Meltwater thaws permafrost and makes rock unstable.

- Matterhorn case study: A rock pillar collapsed in 2023 after years of water ingress.

- SLF research: Long-term measurements and models illustrate how water triggers rockslides.

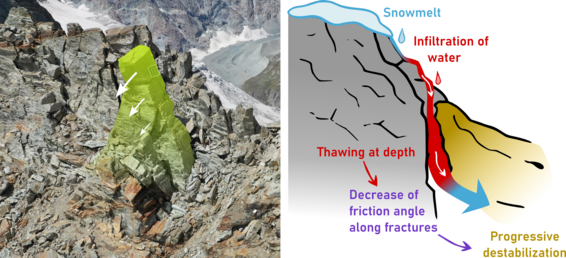

When water penetrates rock crevices in permafrost, it transports heat deep underground, where it causes the frozen rock to thaw. Researchers at the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF) have explored which processes destabilise rock to the point of collapse using a high-profile example: on 13 June 2023, a free-standing rock pillar collapsed on the Hörnligrat, the most prominent access route to the Matterhorn. Around 20 cubic metres of rock fell; fortunately, nobody was injured. For years, water had been seeping into the rock below the pillar during the snowmelt, temporarily thawing and then weakening the rock and so gradually destabilising it. "Climate change is accelerating such processes, which are now a common driving force behind the increasing frequency of rockfalls in high alpine permafrost," says SLF researcher Samuel Weber.

Chain reaction in the rock ¶

The researchers observed and measured the rock pillar for nine years. Their most important piece of equipment in this work was a GNSS receiver (see box). With its help, the researchers were able to record every movement of the pillar down to the millimetre. They compared this measurement series with seismic signals (see box), time-lapse images and laser recordings, among other things. Using rock samples taken from the Hörnligrat as a basis, they studied the rock pillar in a laboratory as part of an international project. "Permafrost thaw significantly reduces the critical angle of friction at which a rock mass starts to move," explains Weber. He transferred his findings to a computer model. This was a success, as the simulation reproduced the measured movements on the Matterhorn one-to-one.

Three effects are exacerbating instability. Due to climate change, the ice in the permafrost that had previously sealed the rock is melting. This allows water to penetrate deeper, putting pressure on the rock. At the same time, the water brings about warmer temperatures underground. This is a chain reaction, because it causes the permafrost and ice to thaw even faster – which in turn allows the water and thus the heat to penetrate even deeper. "This also reduces friction at the fracture point by up to 50 per cent, which further weakens the rock," says Weber.

What is...a GNSS?

A global navigation satellite system (GNSS) enables precise positioning on Earth. 'GNSS' is an umbrella term for systems such as GPS in the US and Galileo in Europe. Such systems comprise numerous satellites that transmit their exact positions from orbit to the Earth's surface. A receiver (e.g. a navigation device in a car) combines signals from several satellites to determine its precise position.

Ten days before the collapse ¶

The interplay of these effects was made spectacularly apparent on the Hörnligrat. The rock pillar had been slowly tilting for years, with this process speeding up from 2022 onwards. "Time-lapse photographs document a visible acceleration in the ten days before the collapse in June 2023," says Weber. At the same time, three seismometers in the vicinity provided evidence of the dynamics of the impending collapse. "Weather data and temperatures in the permafrost indicate that infiltrating water caused rapid, short-term thawing underground and played a major role in the event," clarifies Weber.

What are...seismic measurements?

Seismometers are sensitive devices that record wavelike movements through the ground. Similar to a doctor using a stethoscope to listen to sounds inside a person's body, researchers use seismic measurements to obtain information about what is happening underground. This allows them to analyse not only earthquakes, but also avalanches and landslides – and in some cases even provide early warnings of such events.

With a view to better assessing the risk of rockslides in permafrost, Weber wants to learn more about the interaction between temperature, water and ice in frozen rock and its mechanical effects. To do this, he needs more data. "We're now focusing on the role of water and are combining various measurement methods to this end."

What is ... permafrost?

Permafrost is ground such as rock, debris or moraine that has temperatures below 0°C throughout and is therefore permanently frozen. Permafrost covers some five percent of Switzerland’s territory and is mainly found in scree slopes and rock walls in cold locations at elevations above 2,500 metres above sea level.

Links ¶

The study Progressive destabilisation of a freestanding rock pillar in permafrost on the Matterhorn (Swiss Alps): Hydro-mechanical modelling and analysis is available for download here (in English only).

Contact ¶

Copyright ¶

WSL and SLF provide image and sound material free of charge for use in the context of press contributions in connection with this media release. The transfer of this material to image, sound and/or video databases and the sale of the material by third parties are not permitted.