02/11/2022 | Logbook

Daring Swiss pioneers took exciting photos and observations of glaciers in the Indian Himalayas in the 1930s. Glaciologists from WSL and the universities Zurich and Garhwal now repeated their trip to collect up-to-date data.

14.09.2022 –Swiss explorers in Indian Himalaya

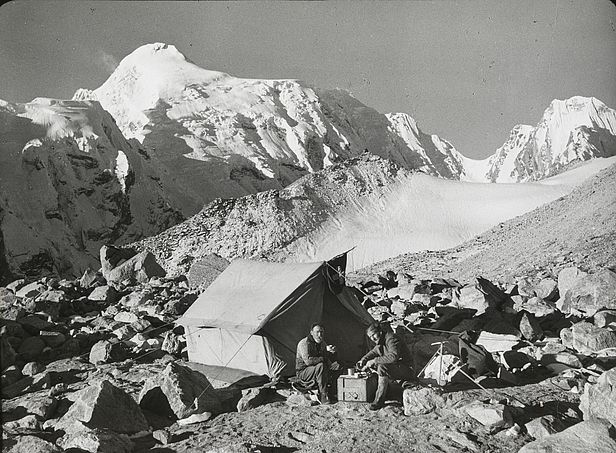

Six Swiss pioneers explored the hidden valleys of the Garhwal range of the Indian Himalaya more than eight decades ago. They made impressive first ascents, survived terrifying avalanches, and most interestingly, made some extremely accurate observations and photographs of the glaciers flowing down these remote ranges.

Their data presents a unique opportunity to understand and quantify the long-term glacier changes in a mountain range where such observations are otherwise inexistent. Simone and myself are about to retrace the steps of these early expeditions, repeat their observations and take additional modern measurements of these glaciers that are strongly impacted by climate change.

19.09.2022 – Picardie weather in the Upper Alaknanda

The rain started as soon as we took our first steps on the approach trek, reminding me of December at my grandma’s place in Picardie in northern France. This year the monsoon had decided to extend its stay in the Upper Alaknanda. Heavy rain and dense fog accompanied us during the whole trip. Some plans had to be adapted, but overall we carried out our measurements as planned, starting with the installation of a gauging station in the proglacial stream of Satopanth Glacier to monitor the discharge and use the data to validate the melt model that we plan to apply in this catchment.

20.09.2022 – Everything looks easy on Google Earth

An important part of this trip was to revisit the glaciers explored by the Swiss explorers in 1936 and 1939, including a remote 5400m peak above Bhagirath Kharak Glacier. For this, we had a clear technological advantage. A few minutes of scrolling on Google Earth and we knew precisely where we would camp, which route we would take, where we would find water, and so forth, on a glacier that has only been visited a handful of times since 1936. ‘See… it’s just 15 km, you walk around the moraine, take foot on the glacier, circumnavigate these ice cliffs and go up this ramp to reach first camp… easy!’

Easy? The only easy thing is to forget how difficult it is to navigate on a debris-covered glacier… Roller coaster hills of unstable boulders, huge supraglacial lakes barring the way when least expected, nasty-looking moraines preventing any passage… We did manage in the end, and some of the historical images could be repeated, which will help reconstruct the long-term changes of these glaciers.

29.09.2022 – Data, data, data!

At last, the sun has returned. Suddenly, everything looks possible, and suddenly we realize that there is still so much data that we want to collect and so little time left. A few minutes after breakfast the drone is already buzzing in the air to map the glacier surface with accuracy to the centimeter, I am running across the debris to measure the position and melt of my ablation stakes, Boris is in the ice cliff channel taking his first scans of the day. All these measurements, repeated several times during the expedition, will tell us how fast the glacier is melting and how variable this melt is. This is crucial data for our understanding of the processes taking place at the glacier surface and for calibrating our glacier melt models.

This final day is a great conclusion to our adventures. We bring back lots of data and exciting stories from this trip, but above all this has been the start of a great collaboration with our colleagues from the University of Garhwal – we know that we will come back to visit them!